.jpg)

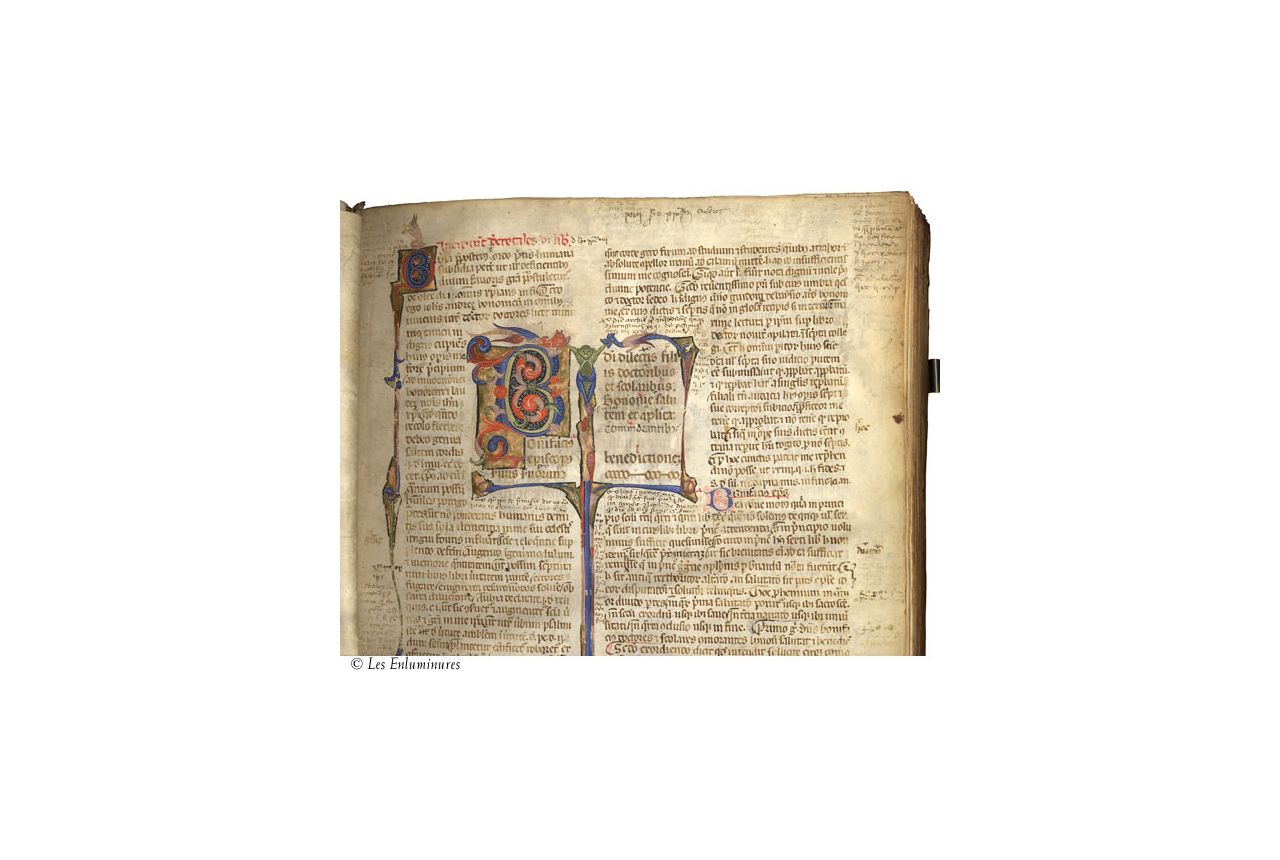

If left in damp conditions, parchment can become gelatinous. Medieval books began as animal pelts that were scraped, stretched, and dried into parchment-a highly-stressed material that is deeply sensitive to changes in humidity. The cycle of mutation for medieval books continues today, even at the most fundamental stratum. The so-called Spanish Forger scraped the music from a portion of a leaf excised from a medieval choir book and painted an illuminated miniature in the resulting blank space. Others were even forged using authentic materials, which both fed and took advantage of the growing market for illuminated medieval manuscript fragments. Some medieval illuminations were “improved”-retouched to fit contemporary tastes. Books were also “perfected” with the addition of illustrations to manuscripts where they had gone missing. Other collectors reconfigured pieces excised from larger contexts into stand-alone objects by framing these cuttings as isolated paintings, perhaps emboldened by the medieval convention of enclosing miniatures in frames and borders. In the nineteenth century, some collectors cut decorated initials and miniatures from medieval books, often pasting them into scrapbooks to create new assemblages, many of which were, in their turn, eventually cut up and dispersed. Many fifteenth- and sixteenth-century devotional manuscripts contain cuttings from earlier illuminated manuscripts and woodcuts. In the following centuries, book owners continued to deconstruct and reconstitute books.

They adhered scraps of outdated manuscripts to the bindings of books to strengthen them, or scraped existing text off of parchment in order to write something new in its place. Medieval manuscript owners also updated their books by repainting illustrations or embellishing pages with decorations cut from earlier manuscripts. (The blank spaces of modern paragraph indentations would likely appear incomplete to medieval readers, who would expect to see decorated initials in a finished work.) For example, the blank spaces left in unfinished books tell us that text was written first and colored initials and other decorative elements were to be added afterwards. In fact, ruling lines were so important to the appearance of a finished medieval book that they continued to be drawn in books even after the advent of print made them functionally obsolete.īooks left unintentionally unfinished by their medieval creators expose many facets of the book-making process-design decisions, technical choices, and raw materials. Like margin notes, visible ruling lines also unsettle the “finished” version of a text for modern readers, but were often part of the planned design of the medieval page. Even in the lavish coronation book seen on the following page, a note in the margin explains that the queen should be crowned and consecrated before the Mass. Although modern readers tend to avoid writing in the margins of books for fear of spoiling them, medieval readers expected annotations. Empty margins were made to be filled not only with decorative borders but also with corrections and glosses added by the scribe and later readers. In fact, “unfinished” space was built into virtually every medieval manuscript. They challenge us to fill in blank spaces with our imaginations, to consider how rough outlines reveal creators’ thought processes, and to absorb the gradations and dissonances between the finished and unfinished sections of a work.

11, based on Colker's notes).Though we valorize completion, unfinished works also have a powerful allure. Have Rosenthal's notes ('Manuscripts from the Collection of Professor Bernhard Bischoff', p. He believed that the fragment came from an adaptation of the text printed in 1480 however, the Catholicon's popularity meant that it was often abridged and adapted. In a letter dated Colker wrote that he had compared the fragment to the reprint of the 1480 Mainz edition and found that explanations of words were similar and some of the text were similar but "there is much divergence" between the printed text and the fragment. One side contains ordior and the other opusculum. 1298) Catholicon covering nouns beginning with the letter 'O'. Small Cursive.ĭate, place, and text identified by Bischoff in pencil note (now missing?) John Balbus' (d. Column and line ruling in lead (?) Rubrication.

#Ruling width medieval manuscripts full

Originally 2 columns, fragment contains 1 full column on each side plus approx 1/3 of another column.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)